Pediatric asthma

Introduction

Although asthma is a common disease, it is not always recognized that asthma has become the most common chronic disease of childhood. Symptoms of wheezing, coughing and/or shortness of breath are indeed common among infants and children. While these symptoms, when caused by asthma, usually respond well to appropriate medications, the exact diagnosis is not always obvious early in the evaluation of such patients.

Distinctive features

Asthma is more likely to be episodic in children and persistent in adults. Children tend to be more allergic than adults, with elevated IgE levels and positive skin tests. Allergic childhood asthma is often associated with diseases such as food allergy and/or atopic dermatitis. Children may develop hyperinflation more rapidly than adults. The FEVâ‚ values (measurements of lung function) at all severity levels can return to normal levels when they are clinically stable, and these asthmatics usually respond well to bronchodilators. Early in childhood, small airways are frequently affected with an increase in peripheral airway resistance without significant large airway involvement. Commonly, there is a shift between early infancy or childhood and later childhood or adolescence marked by an increased degree of large airway involvement.

Common patterns

Wheezing in infants and young children can be divided into three specific groupings:

RiskFactors

The Asthma Predictive Index (or risk factors for asthma) includes: a history of: atopic dermatitis (eczema), allergic rhinitis, parental asthma, wheezing occurring without a viral upper respiratory infection, and blood eosinophilia greater than 4%. The incidence of asthma can rise to 40% in infants admitted to a hospital with RSV respiratory infections, such as bronchiolitis. Children with evidence of IgE-mediated disease will more likely have persistent wheezing than those without allergy.

- Viral infections

- Environmental allergens

- Irritants (e.g., smoke exposure, chemicals, vapors, dust)

- Exercise

- Emotions

- Home environment (e.g., carpets, pets, mold)

- Stress

- Drugs (e.g., aspirin, beta blockers)

- Foods

- Changes in weather

- Other conditions (e.g., thyroid disease, adolescent pregnancy, menses, gastroesophageal reflux disease/GERD, sinusitis, rhinitis)

- Dust mites

1. Infection

More than 80% of infant hospitalizations due to asthma result from viral respiratory tract infections. Respiratory syncytial virus is considered the most common viral cause of wheezing in infants. Metapneumovirus is a newly identified cause of cold weather exacerbations of asthma in children, causing prolonged hospitalizations. In addition, other investigators have also identified the rhinovirus as a frequent culprit.

2. GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a common cause of wheezing in infants under 1 year of age. Studies of bronchoalveolar lavage samples in infants with asthma have revealed evidence of inflammation with increased neutrophils, macrophages, IL-8, and myeloperoxidase which suggest aspiration associated with gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). It has been shown that treatment of GERD will substantially reduce asthma medication requirements in affected patients. GERD is also a common co-morbid disease in difficult-to-manage asthma and should always be ruled out in such cases.

3. Allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, and upper respiratory tract infections ( URTI )

Inflammatory conditions of the upper airways (e.g., allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, or chronic and persistent infections) should be treated in order to better control asthma symptoms. Inflammation of the upper airway can provoke lower airway symptoms. In other words, in asthma, what affects the upper airway also can affect the lower airway. For example, chronic sinusitis can worsen asthma in spite of appropriate asthma treatment.

4. Passive smoke inhalation

It is known that passive cigarette smoke triggers asthma and may lead to an increase in airway responsiveness in infants. Up to 13% of asthma in children under 4 years old is reportedly due to exposure to maternal smoking. Even fetal smoke exposure is linked to childhood asthma. The childhood consequence of asthma is a risk factor for adult asthma.

5. Allergy

The development of allergy is also a significant trigger of asthma. Recent studies by Delacourt et al and Wilson et al have shown that wheezing children under 3 years old had positive skin testing to dust mites, cat, or cockroach in 30-45% of those tested. Outdoor allergens have also been implicated, such as grass or other pollen with positive skin testing in young children and infants. The earlier the sensitization, the higher the risk for subsequent asthma in adolescence. Worst of all is the persistence of indoor allergen exposure including dust mites, cockroach, cat and dog dander, and less often, mold. Chronic exposure to these allergens in a sensitive asthmatic makes it very difficult to bring the child’s symptoms under good control. This may lead to steroid dependence because of frequent flares of symptoms leading to many emergency visits and hospitalizations.

6. Outdoor and Indoor Air Pollution

Outdoor air pollution exacerbates asthma, increasing emergency room visits and hospitalizations among children with asthma.

- Dry, hacking cough

- Wheezing

- Dyspnea

- Chest tightness or discomfort

- Nocturnal chest symptoms

- Exercise intolerance or poor sports performance

- Persistent cough or chest symptoms following a URTI

- Cold air-induced dyspnea,

coughing or wheezing - Coughing or dyspnea due to crying, yelling or singing

Diagnosis and evaluation

Early recognition of various risk factors in pediatric asthma (including information derived from the family history), is crucial. The importance of a comprehensive environmental history cannot be overstated, as it indicates which environmental changes will improve symptoms and alter the course and severity of the child’s asthma (to learn more about practical environmental changes, visit TheAsthmaCenter.org). For example, consider the child’s primary environment (their home(s), relatives’ homes, school, day care, sports, etc.) to which the child is exposed. A history of wheezing with exposure to pets, foods, or indoor or outdoor allergens is an indication for allergy testing.

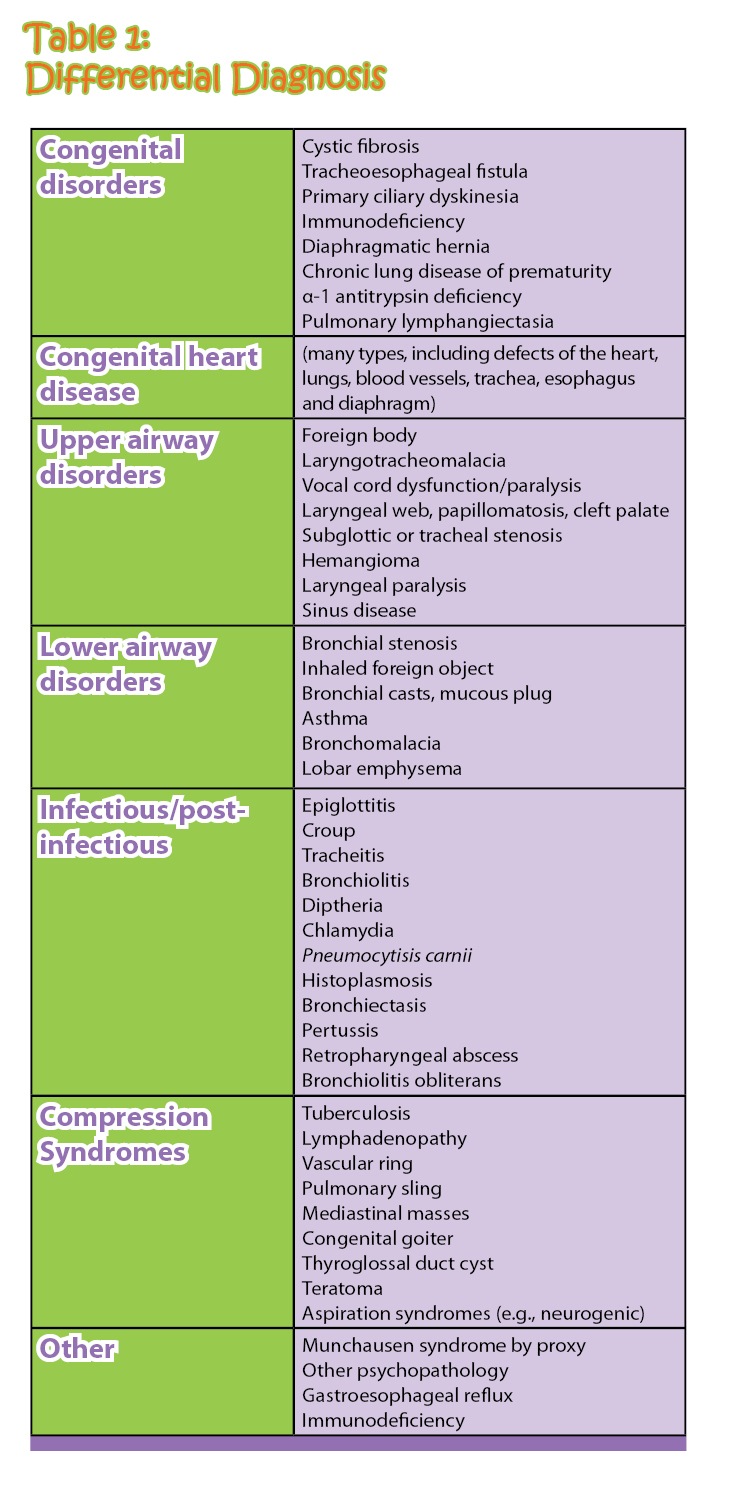

Congenital disorders

Cystic fibrosis, tracheoesophageal fistula, primary ciliary dyskinesia, immunodeficiency, diaphragmatic hernia, chronic lung disease of prematurity, a-1 antitrypsin deficiency, pulmonary lymphangiectasia

Congenital heart disease

(many types, including defects of the heart, lungs, blood vessels, trachea, esophagus and diaphragm)

Upper airway disorders

Foreign body, laryngotracheomalacia, vocal cord dysfunction/paralysis, laryngeal web, papillomatosis, cleft palate, subglottic or tracheal stenosis, hemangioma, laryngeal paralysis, sinus disease

Lower airway disorders

Bronchial stenosis, inhaled foreign object, bronchial casts, mucous plug, asthma, bronchomalacia, lobar emphysema

Infectious/post-infectious

Epiglotitis, croup, tracheitis, bronchiolitis, diptheria, chlamydia, Pneumocytisis carnii, histoplasmosis, bronchiectasis, pertussis, retropharyngeal abscess, bronciolitis obliterans

Compression syndromes

Tuberculosis, lymphadenopathy, vascular ring, pulmonary sling, mediastinal masses, congenital goiter, thyroglossal duct cyst, teratoma

Other

Munchausen syndrome by proxy, other psychopathology, gastroesophageal reflux, immunodeficiency

- Increasing shortness of breath with inadequate response to medication

- Frequent use of beta agonist inhaler (rescue inhaler) > 5x/day with inadequate relief

- Use of accessory muscles

- Chest pain

- Presence of cyanosis

- Dyspnea interfering with feeding or speaking

- 2nd acute asthma attack following release from ER

- Persistent vomiting associated with severe cough

1. GERD

2. Chronic sinusitis

3. Chronic allergy

Differential Diagnosis

Evaluation of a child or infant with asthma-like symptoms needs to objectively define the type and severity of the asthma while also considering the broad differential diagnosis that exists in the pediatric patient.

A sweat test is recommended for infants and young children with asthma symptoms to rule out cystic fibrosis, which can easily mimic this disease.

If the child has a history of recurrent, severe or unusual infections, an immunodeficiency workup is necessary.

Selective allergy skin testing for aeroallergens and food allergens can be helpful in the early diagnosis and treatment of allergic asthma since antigen-specific IgE triggers can begin between 1 and 3 years of age. Although allergen induced asthma is uncommon during the first year, its prevalence increases in childhood and adolescence.

1. Education

Patients/caretakers must learn how medications work, their correct administration, and the proper order of use. Each patient must have an individualized emergency action plan with all necessary medications immediately available. Further, the patient or caretaker needs the knowledge and tools to assess asthma control, monitor for medication side effects, and the ability to recognize a developing asthma emergency. Education comes in many forms, however, the best way to ensure proper medication use and optimum asthma control is for the patient to be audited and educated by asthma specialists on a regular basis.

2. Allergen avoidance

Dust mite avoidance has been noted to have a modest treatment effect in infants. However, mattress encasing has helped significantly lower the necessity for steroid medications in older children. Read more about environment controls for those suffering from allergic asthma and respiratory allergy at TheAsthmaCenter.org.

3. Medications

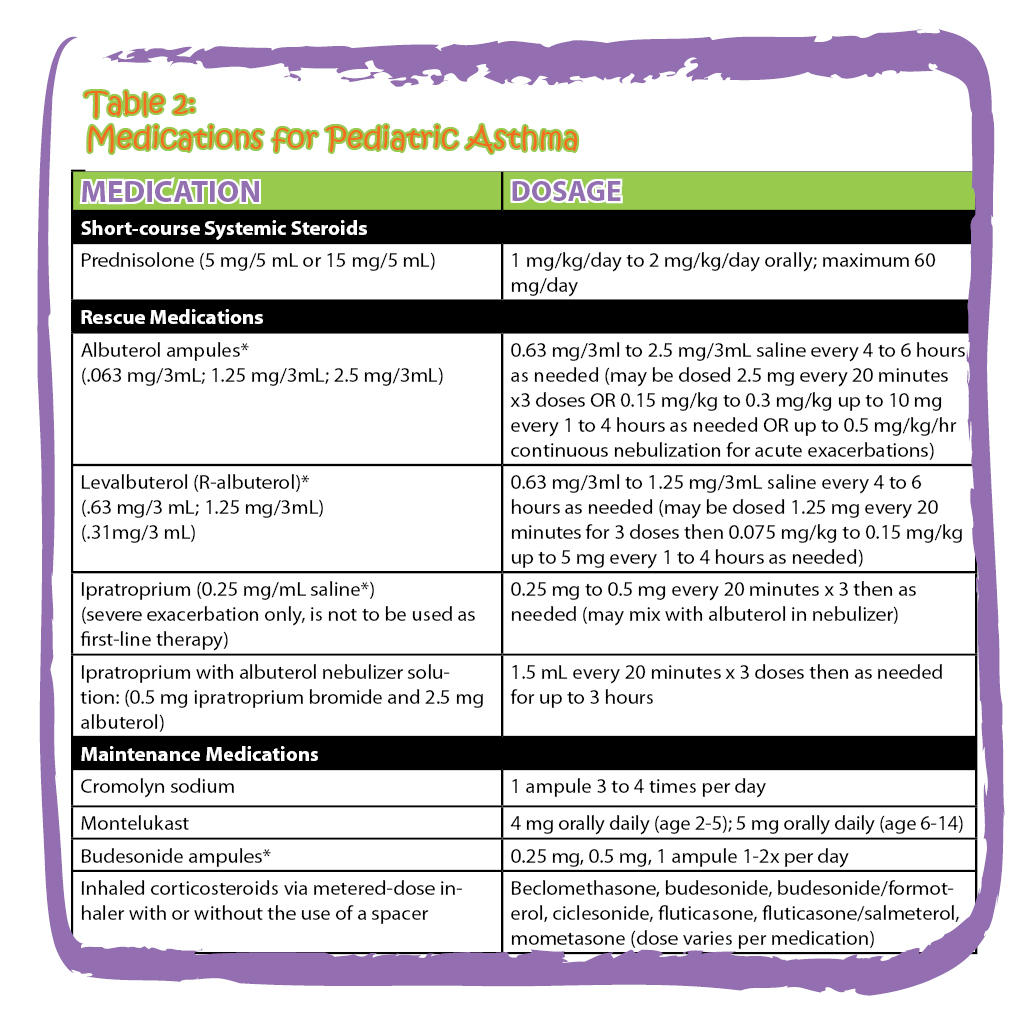

β-2 agonists are among the most frequently used bronchodilators. They are easy to administer via nebulizer or MDI with or without a spacer. β-2 agonists are appropriate for infants and young children. Infants and all children who have a history of acute flares of asthma should have a nebulizer available to them in order to avoid ER visits and hospitalization. Side effects include: irritability, sleep disturbances and behavioral changes. These symptoms are dose-dependent and reversible. Moreover, oral forms are more likely to cause these side effects in susceptible individuals. Continuous nebulization has been effective in severe, acute asthma when intermittent use is ineffective. Long-acting β-agonists are approved for children over 4 years of age for persistent asthma, but they must always be used along with inhaled steroids.

Anticholinergic agents have been useful as additional medications in severe infant or childhood asthma exacerbations. Ipatropium bromide is a quaternary isopropyl product derived from atropine that is available as a nebulizer solution (0.25mg/ml of saline) or as a metered dose inhaler. In a current NHLBI statement, there is a recommendation that ipatropium is appropriate to use during severe exacerbations in infants as an additional treatment.

Cromolyn sodium has been available since the 1970s as an anti-inflammatory medication that inhibits degranulation of mast cells and inhibits early and late-phase asthmatic reactions to allergens. Due to its significant safety profile and lack of toxicity, it is used in young children for chronic treatment. However, it is reportedly less effective than low-dose inhaled steroids for asthma control. In addition, it is not recommended as a first-line treatment for infants and young children with chronic asthma. Since the metered dose inhaler is no longer available, nebulized cromolyn sodium is currently used in children over 1 year of age. Cromolyn is currently used by most clinicians to: 1) prevent wheezing in infants and young children as a maintenance medication; 2) to prevent allergen-induced asthma; and 3) when parents are very reluctant to treat with corticosteroids. It prevents asthma symptoms when administered prior to allergen exposure, as it blocks mast cell degranulation which triggers asthma in allergic children.

Leukotriene antagonists such as montelukast block the inflammatory effects of leukotrienes, which are chemical mediators of bronchospasm, inflammation, eosinophilia, stimulation of mucus secretion, and increased vascular permeability. This drug is approved for children 12 months and older with a dosage of 4 mg in granules for children aged 12-24 months; 4 mg for 2-5 years; 5mg for 6-14 years and 10 mg for above 15 years. Studies have shown that young children and infants improved symptom scores and nitric oxide production, although inhaled steroids were more effective.

The NHLBI guidelines list inhaled corticosteroids as the preferred first-line treatment, but montelukast is mentioned as an alternative or add-on therapy for mild-persistent to more severe asthma. Many parents prefer the use of a tablet or granule preparation as a long term controller medication in place of a corticosteroid. However, many asthmatics will not respond adequately to leukotriene antagonists, while almost all will benefit from an inhaled corticosteroid with rare significant side effects. In some patients, there may be a synergy when inhaled corticosteroids are administered along with a leukotriene antatagonist. Steroid phobia remains an important issue that needs to be addressed with some parents.

Theophylline has been used for decades, but is now in limited use due to concerns about side effects including nausea, insomnia, agitation, cardiac arrhythmias and seizures. Serum monitoring is essential in order to achieve therapeutic levels between 5-15 mg/dl. Metabolism changes must be recognized with age, diet, fever, viral infections and drug interactions in order to avoid side effects. The NHLBI guidelines continue to list Theophylline as an alternative or added therapy for children under 4 years of age due to its proven efficacy. Theophylline’s narrow therapeutic window along with its potential for serious toxic side effects and need for frequent monitoring make it an uncommon choice for the treatment of asthma because of the superiority of currently available alternatives.

Corticosteroids remain one of the most potent treatments due to their anti-inflammatory effects. These medications reduce mucus production, decrease mucosal edema, decrease inflammatory mediators and increase β-adrenergic responsiveness. Corticosteroids improve lung function, reduce airway hyperreactivity, and reduce the late-phase asthmatic response. As a maintenance therapy, inhaled steroids provide the desired anti-inflammatory treatment without significant side effects, particularly compared to oral steroid use or frequent bronchodilator treatments.

Numerous studies have shown that Budesonide (Pulmicort) and Fluticasone HFA MDI (Flovent HFA MDI) via spacer and face mask have improved pulmonary function, symptom scores and quality of life. The NHLBI guidelines indicate that inhaled steroids are the initial drug of choice in asthmatic children younger than 4 years of age. Although some studies have shown a short-term linear growth decrease in children on inhaled steroids (Budesonide and Fluticasone), catch-up growth occurs after the first year or during puberty. Current studies have not shown clinically significant adrenal suppression in infants or small children. A newer inhaled steroid, ciclesonide (Alvesco HFA) is being studied in young children due to its lower bioavailability and decreased potential for side effects. This newer generation inhaled steroid virtually eliminates systemic effects which could end concern over growth in children. The choice of inhaled steroid depends on potency, systemic absorption, taste, delivery system, and cost. Therapy must be individualized for each patient and for each pattern of disease activity.

4. Allergen Immunotherapy

Despite the use of inhaled steroids, asthma management in some children remains a problem. The significant role of aeroallergens in pediatric asthma suggests that allergen immunotherapy might provide a more permanent disease-modifying outcome after medical treatment is discontinued. Further, immunotherapy can decrease bronchial sensitivity and result in a lower need for medications. In older children, a 3-year course of subcutaneous immunotherapy with standardized allergen extracts has demonstrated long-term clinical effects. In addition, subcutaneous immunotherapy has shown its potential to prevent development of asthma in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. This clinical effect was noted up to 7 years after treatment. However, subcutaneous immunotherapy in very young children is problematic due to the child’s inability to verbalize or cooperate. Sublingual immunotherapy might be better tolerated in young children, however its efficacy is not yet fully demonstrated and it is not an approved therapy by the FDA as safe and effective at this time. Further studies are needed to determine the role of immunotherapy in altering the natural history of asthma in young children.

Prognosis

In infants with wheezing, there is a 15% incidence of persistent symptoms after the age of 3. Risk factors that predict persistent symptoms beyond infancy include males, presence of atopy, passive smoke exposure, and a parental history of asthma.

Conclusion

Although asthma is the most frequent chronic disease in childhood, its diagnosis and optimum treatment remain a challenge to the clinician. In many young children, early treatment of small airway disease before asthma becomes difficult to control, may be increasingly important. The NHLBI guidelines stress that some patients can still be at risk for frequent or severe exacerbations even if they have few daily symptoms. The clinician’s goal is to increase the quality of life of each asthma patient while decreasing morbidity and mortality.